Some of my favorite experiences in writing the book were learning about truly independent citizen science projects. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not denigrating the projects that are sponsored by institutions. Good work is good work, after all, and as a practical matter, institutions are an effective way to ensure that things get done on a continuing basis.

It can be tough to make things happen and keep them happening without an institutional framework. In writing the book, I was really impressed by the projects that developed independently, just because some individual was interested in something and wanted to learn more.

Ken Strothkamp’s research into the spotted tussock moth is one of those projects. It started when his daughter found a moth he couldn’t identify. He turned to the Butterflies and Moths of North America website for assistance; there he learned not only what the moth was, but also that it hadn’t been documented in their county before. They were able to see the difference that their discovery made in the species’ range maps, and from there they were hooked.

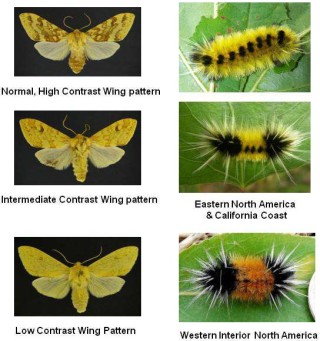

Ken is a researcher at Lewis & Clark College in Portland Oregon, but he knew nothing about butterflies or moths when he started investigating. In particular, he was curious about regional variations in coloring in the spotted tussock moth’s caterpillar. In eastern North America and along the California coast, the caterpillar is yellow and black, but in the interior west it’s orange and black. The Pacific Northwest population has significant variation in coloration.

While Ken has formal scientific training and access to a lab, he also has more than 50 citizen contributors who share observations, photos, and specimens. He produces an annual report for those contributors, and he gave me permission to share some of the most recent results with you.

The project has made progress in identifying several of the pigments that make up the various colors of the caterpillar—zeaxanthin, a yellow pigment that it gets from its food; and eumelanin, a black pigment it makes itself (also the pigment which is found in black human hair). An orange pigment in the caterpillar remains unidentified, but it may be the same one found in red hair in humans.

Ken has theorized that the Pacific Northwest population is a hybrid of the western interior and coastal California forms made possible when the climate warmed after the last ice age and the species migrated north. He has demonstrated the possibility of this theory by hybridizing the two variants in the lab. These hybrids showed the same color variations as wild spotted tussock moths in the Pacific Northwest.

The research has raised other questions. These include:

- The cause of a rare white phenotype of the spotted tussock moth, in which the caterpillar will lose some of its pigmentation during its fourth instar (developmental stage; each caterpillar undergoes five in total) but its coloration will be normal as an adult moth.

- How different populations hybridized when the coastal California variation has two generations per year but other varieties breed only once annually, which reduces the period when both varieties have adults flying at the same time.

- Whether the production of black dorsal spots in the fifth instar in some regions but not others provides further evidence of hybridization.

Whether a newly discovered caterpillar color variant (white with a yellow central region with black spots, as pictured) reverts to more typical coloration, what causes it, and if it’s a unique individual or if there are others like it.

Whether a newly discovered caterpillar color variant (white with a yellow central region with black spots, as pictured) reverts to more typical coloration, what causes it, and if it’s a unique individual or if there are others like it.

For more details and to contribute to the project, contact Ken at kenstrothkamp@lclark.edu.